share on

To prevent heat stress, employers and employees must be able to recognise and understand the source of heat and how the body removes excess heat.

According to the Malaysian Meteorological Department's (METMalaysia) update on Tuesday (16 May 2023), four areas in Peninsular Malaysia have been issued a Level 1 (yellow, 'be careful') heat warning.

In particular, these areas – Pasir Mas, Kuala Krai, Rompin, and Muar – have reached this level after facing a daily maximum temperature of 35-37°C for at least three consecutive days.

For reference, there are three warning levels to note, with the remaining two being:

- Level 2: daily maximum temperature of between 37-40°C (orange, 'heatwave') for at least three consecutive days.

- Level 3: daily maximum temperature exceeding 40°C (red, 'extreme heatwaves') for at least three consecutive days.

Per a report by The Star, Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Ahmad Zahid Hamidi has shared that at the moment, Malaysia has no plans in place to declare an emergency in light of the ongoing heat situation.

He was quoted as saying: "We have put in place proactive and preventive measures such as cloud seeding to face the heatwave. For now, we don’t think there is a need for an emergency to be declared.

“But if need be, we will issue Directive 20 of the National Security Council for an emergency to be called."

In that vein, the National Disaster Management Agency in Malaysia has just shared an update on METMalaysia's weather forecast across the country from today (17 May) to Friday (19 May):

Ramalan cuaca @metmalaysia bagi seluruh negara pada 17 Mei 2023 – 19 Mei 2023#KesiapsiagaanBencanaTanggungjawabBersama pic.twitter.com/8Eu3puYZ0T

— NADMA Malaysia (@mynadma) May 17, 2023

In view of the current heat situation in Malaysia, HRO has put together a quick guide covering extracts from the Department of Occupational Safety and Health's Guidelines on Heat Management at the Workplace (2016). At the time of writing, this is the latest set of guidelines in place.

Factors that contribute to heat stress

Many factors contribute to heat stress. To prevent heat stress, employers and employees must be able to recognise and understand the source of heat and how the body removes excess heat. The most commonly used indicator of heat stress is air temperature. However, air temperature alone is not a valid or accurate indicator of heat stress.

Instead, it should be always considered in relation to other environmental and personal factors. These factors may be independent, but together can contribute to an employee’s heat stress.

Environmental factors

Air temperature: The temperature of the air surrounding the body. It is usually given in degrees Celsius (°C).

Air velocity: This describes the speed of air moving across the employee and may help cool them if the air is cooler than the environment. Air velocity is an important factor in heat stress.

For example:

still or stagnant air in indoor environments that are artificially heated may cause people to feel stuffy. It may also lead to a build-up in odour.

moving air in warm or humid conditions can increase heat loss through convection without any change in air temperature.

physical activity also increases air movement, so air velocity may be corrected to account for a person’s level of physical activity.

small air movements in cool or cold environments may be perceived as a draught as people are particularly sensitive to these movements.

Radiant temperature: The heat that radiates from a warm object. Radiant heat may be present if there are heat sources in the environment. Radiant heat can affect people who are exposed to direct sunlight or close to the process area which emits heat.

Examples of radiant heat sources include: the sun, fire, heaters, kiln walls, cookers, dryers, hot surfaces and machinery, boilers, furnaces molten metals, etc.Relative humidity: The ratio between the actual amount of water vapour in the air and the maximum amount of water vapour that the air can hold at that air temperature. Relative humidity between 40% and 70% does not have a major impact on heat stress.

In workplaces that are not air-conditioned, or where the weather conditions outdoors may influence the indoor heat environment, relative humidity may be higher than 70%.

Non-environmental factors

Personal factors:

- Clothing

- Health conditions

- Acclimatisation

- Hydration

Work factors:

- Metabolic heat

- Work rate (light/moderate/heavy)

Groups of employees and industries affected

Employees exposed to hot indoor environments or hot and humid conditions outdoors are at risk of heat-related illness, especially those doing heavy work tasks or using bulky or nonbreathable protective clothing and equipment.

Some workers might be at greater risk than others if they have not built up a tolerance to hot conditions, including new workers, temporary workers, or those returning to work after a week or more off or if they have certain health conditions.

Some environmental and job-specific factors that increase the risk of heat-related illnesses include:

Environmental:

- High temperature and humidity

- Radiant heat sources

- Contact with hot objects

- Direct sun exposure (with no shade)

- Limited air movement (no breeze, wind, or ventilation)

Job-specific:

- Physical exertion

- Use of bulky or non-breathable protective clothing and equipment

The following table details the activities exposed to heat, by economic sectors:

Types of heat-related illness

Heat rash: Heat rash is the most common problem in hot work environments. It causes discomfort and itchiness, is caused by sweating, and looks like a red cluster of pimples or small blisters.

Heat rash may appear on the neck, upper chest, groin, under the breasts, and elbow creases.

Heat cramps: These are muscle pains usually caused by the loss of body salts and fluid during sweating. Workers with heat cramps should replace fluid loss by drinking water and/or carbohydrate-electrolyte replacement liquids (e.g. isotonic drinks) every 15 to 20 minutes.

Heat exhaustion: This is the next most serious heat-related health problem. Heat exhaustion is the body’s response to an excessive loss of water and salt, usually through excessive sweating.

Signs and symptoms include: headache, nausea, dizziness, weakness, irritability, confusion, thirst, heavy sweating, and a body temperature greater than 38°C.

Heat syncope: Heat syncope is a fainting (syncope) episode or dizziness that usually occurs with prolonged standing or sudden rising from a sitting or lying position. Factors that may contribute to heat syncope include dehydration and lack of acclimatisation.

Symptoms include: light-headedness, dizziness, and fainting.

Heat stroke: This is the most serious form of heat injury and is considered a medical emergency. Heat stroke results from prolonged exposure to high temperatures and is usually in combination with dehydration, which leads to failure of the body’s temperature control system. The medical definition of heat stroke is a core body temperature greater than 40.5°C, with complications involving the central nervous system that occur after exposure to high temperatures.

Other common symptoms include: nausea, throbbing headache, seizures, confusion, disorientation, and rapid, shallow breathing.

Heat stroke can cause death or permanent disability if emergency treatment is not given.

Evaluating the risk of heat-related stress

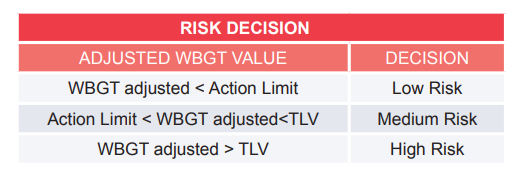

The risk of heat-related stress depends on the wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT), i.e., the most widely used and accepted index for the assessment of heat stress in the industry.

In general, the following criteria can be used to make a decision on the severity of the risk.

Low risk: There is minimal risk of excessive exposure to heat stress.

Medium risk: Implement general control, which includes drinking of water and pre-placement medical screening.

High risk: Further analysis may be required. This may include monitoring heat strain (physiological responses to heat stress), and signs and symptoms of heat-related disorders. In addition, job-specific control should be implemented.

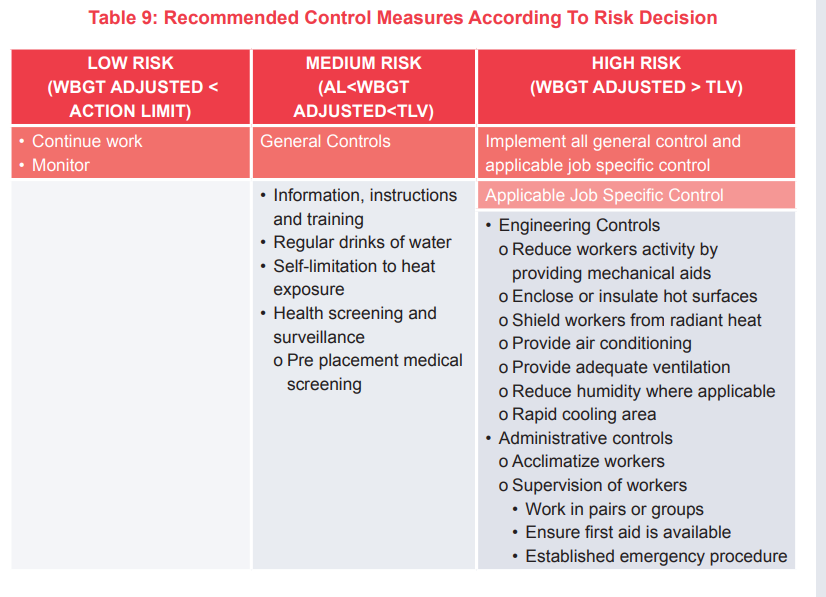

Based on the risk decision obtained, employers are advised to implement the respective preventive and control measures, as follows:

The guidelines also outline the acclimatisation process, in which an individual's body adjusts to a graduate change in environment, allowing it to maintain performance across a range of environmental conditions. It takes, in general, seven to 14 days for this to complete.

Additionally, loss of acclimatisation occurs gradually when a person has moved permanently away from a hot environment. However, a decrease in heat tolerance occurs even after a long weekend. As a result of reduced heat tolerance, it is often not advisable for anyone to work under very hot conditions on the first day of the week.

Next, new employees should acclimatise before assuming a full workload. It is advisable to assign about half of the normal workload to a new employee on the first day of work, and gradually increase the workload on subsequent days. Although well-trained, physically fit workers tolerate heat better than people in poor physical conditions, fitness and training do not substitute for acclimatisation.

Thank you for reading our story! If you have any feedback, feel free to let us know — take our 2023 Readers' Survey here.

Photo: Shutterstock

Infographics & excerpt of guidelines: DOSH Malaysia

share on

Follow us on Telegram and on Instagram @humanresourcesonline for all the latest HR and manpower news from around the region!

Related topics